Joe Arridy - An Innocent Man

I first came across Joe Arridy on a Reddit post. It’s a black-and-white photo, included near the end of this post, of a smiling young man giving a toy train to another man. The caption read something to the effect of: “Joe Arridy, the ‘happiest prisoner on death row,’ gives away his train before being executed, 1939.” The comments gave more information, namely that Joe had the cognitive ability of a six-year-old and was wrongfully executed for the rape and murder of a teenage girl. I have put off writing this post, I will be honest. It is one of the most difficult I’ve done. Joe reminds me so much of students I have worked with and makes me worry for what their future may look like. This post is going to be not uplifting, but it is important. It highlights issues faced by the disability community still today, including racism, homophobia, physical and sexual abuse, intstitutionalization, higher incarceration rates, and the death penalty. Read with care.

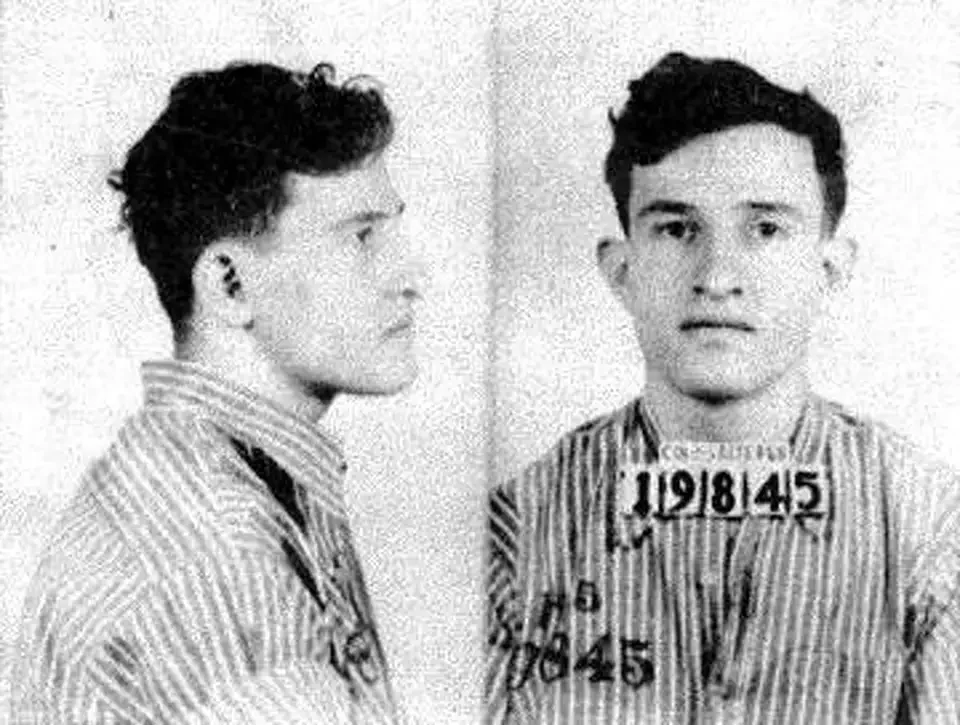

Joseph Arridy (spelled at different times as Areddy, Arddy, Ardy, or Arriag) was born on April 29, 1915 in Pueblo, Colorado. His parents, Mary and Henry Arridy, were Maronite Christian immigrants from a village in Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, Ottoman Syria (modern-day Lebanon). At the time, this region was a part of the Ottoman Empire, which was dissolved after World War I. Being called “Syrian” at this time could mean anyone from the general region of Syria, Palestine, or Lebanon. Before 1899, they were lumped into the group called “Turks.” Beginning in the 1920s, the majority of immigrants from the Mount Lebanon area referred to themselves as “Lebanese.”

These “Syrian” immigrants were in an interesting, and frustrating, racial muddle in America. At the time of the Arridys’ immigration, they would have been considered “Oriental” or “Asian,” as they technically came from western Asia. However, during that first half of the 20th century, many Arabic immigrants fought to be officially recognized as white in order to gain naturalized citizenship. Some courts granted them this eligibility to be “white American” citizens, while others did not. At the same time, others were deported as “non-white aliens.” In 1915, the case of Dow v. United States affirmed that Syrians were white, though this did not include North Africans or Arabs from outside of the Levantine region in the Middle East. And, even with this federal case, many courts still deemed Syrians as non-white. The Immigration Act of 1924 greatly cut Syrian immigration to America for decades, even after 1943, when all Arabs and North Africans were deemed white by the federal government. These quotas were annulled by the Immigration Act of 1965.

Joe’s parents were part of the approximately 90,000 “Syrians” who immigrated to America between 1899 and 1919. Henry immigrated in 1909, by way of Greece, followed by Mary in 1912. The two were first cousins and knew no English. Henry became a molder (a skilled tradesman who creates molds for metal casting) with a Colorado Fuel and Iron steel mill in Pueblo, Colorado.

Their first child was Joseph, always called Joe. He was the oldest of their three surviving children (they lost several other children young). George was born in 1923 and Amelia “Melia” in 1924. Joe was a good-natured child and content to play at home. Since he was an only child until 8 years old, his mother had time to devote to him. His differences soon became apparent: he reportedly was nonverbal until the age of five and, even then, only spoke in short, simple sentences. He usually did not speak unless spoken to, a habit that continued into adulthood. His parents enrolled him in Bessemer Elementary School for first grade, but after one year, the principal told them to keep Joe at home, saying the boy could not learn. (It should be noted that Joe had learned to read a bit, though he never learned how to write more than his name.) Children with disabilities did not have the right to an education until Congress passed PL 94-142 in 1975. After being kicked out of school, Joe enjoyed wandering around town, making mud pies, and hammering nails. He did not socialize with the other neighborhood children. He was described as a passive, quiet loner.

When Joe was ten years old, in 1925, his father lost his job. He turned to bootlegging, meaning he kept odd hours and was also in and out of jail. Mary, home with a toddler and a baby, was unable to supervise Joe. Desperate to find a safe place for his son, Henry began asking neighbors in January 1926 to help him write letters to various institutions. At that time, committing a child with disabilities to an institution was essentially the only choice for families, and was, in fact, highly encouraged. Henry’s neighbors helped him go to the Pueblo District Court that October to commit Joe to the State Home and Training School for Mental Defectives (formerly a boarding school for indigenous children; now the Grand Junction Regional Center). Formal psychological testing detailed that he spoke in 2-3-word sentences, was a very concrete thinker and could not think abstractly, couldn’t count past 5, and couldn’t correctly identify colors or days of the week. He was labeled as an “imbecile” and described as “slow” with a “stupid, distant look.”

Because of the eugenic and racist thinking of the time, the entire immigrant family was also formally tested for intellectual disability. It was concluded that, though Henry was of average intelligence, Mary was “probably feeble-minded” and younger brother George was a “high moron.” While it is possible that they also were disabled, it is impossible to know, as testing was very biased and only given in English.

Henry soon regretted committing his son to this institution. His oldest child was now halfway across the state and was missed by his family. He requested a formal release. The superintendent drafted a letter for Henry to sign, absolving the school of any responsibility for Joe. He finally went home to Pueblo in August 1926. Frustratingly, as if he were being released from prison, Joe was followed by a juvenile probation officer. He was happy to be home and resumed wandering around.

While Henry was in jail for bootlegging, on September 17, 1929, fourteen-year-old Joe was cornered and sexually assaulted by a group of teenage boys. They sodomized him and forced him to perform oral sex on them. Joe’s probation officer walked in on them and broke up the situation. This incident highlights a tragic problem still faced by people with disabilities today: sexual abuse. Because of communication difficulties, lack of education, and dependency on caregivers, they are highly at risk. The organization RAINN reports that people with disabilities are four times more likely to be sexually assaulted than people without, with those with intellectual disabilities at the highest risk. They are the victims of 26% of all nonfatal violent crime. And their sexual assaults are only reported to the police 19% of the time, versus 36% of the time for people without disabilities.

The probation officer immediately wrote a complaint letter to Dr. Benjamin Jefferson, the superintendent of the training school to which Joe had been committed. The officer, though, misrepresented the situation in a devastating way: he claimed that the sexual assault was consensual. The letter was filled with both homophobia and racism (because the assailants were Black and Joe was Asian or white, depending on who you asked). The officer threatened to blame the superintendent for allowing Joe to leave school, saying, “He is one of the worst mental defective cases that I have ever seen. I picked him up this morning for allowing some of the nastiest and dirtiest things done to him that I have ever heard of… The boy MUST be returned. The people of the neighborhood are indignant as they are afraid of the boy and think he never should have been turned loose… I cannot understand why boys of the mentality of this one are allowed to return home.” The officer never faulted the rapists.

Joe was forcibly recommitted to the training school. His family appealed the decision repeatedly, but were told by the superintendent, Dr. Jefferson, that Joe was being kept there for safety reasons due to his “perverse habits.” That referred to pretty much anything sexual. Girls and boys lived separately. All staff members were trained to watch for the “perverse habit” of masturbation and told to do everything to stop it.

The teenager ended up staying there for seven years, during which time he was often mistreated, beaten, and manipulated by peers. He did not function well enough to participate in the farm or school programs there. Initially, Joe spent his time in the day room before being moved to the kitchen to work. There he was taught “tasks of not too long duration,” like mopping, washing dishes, or running simple errands. Dr. Jefferson also noted that Joe was a follower and highly suggestible, citing an incident where he falsely took blame for stealing cigarettes. The boy had no friends, but did become close with Mrs. Bowers, the kitchen worker who supervised him.

Life stayed miserable and monotonous until August 9, 1936. By this time, Joe was a five-foot, four-inch, 130-pound 21-year-old with intellectual disabilities who had not seen his family in seven years. He and four other young men - Clifford Mullins (15), Benny Harvey (15), Jose Francisco (24), and Roy T. Spencer (20) - from the school stowed away in freight trains, just like the train-hopping “hobos” of that Great Depression era. They rode through Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming. The other young men returned to school after a few days, but Joe continued riding the rails.

On August 20, Joe got off in Cheyenne, Wyoming. He was dirty and hungry, so went to the kitchen car of a train and asked for food. The car’s supervisors, Mr. and Mrs. Glen Gibson, allowed him to stay, gave him clean clothes, and let him wash dishes in exchange for meals. They commented that, though he rarely spoke, he did his job well.

The following week, the train was bound to head out of state and, since he was not an official employee, Mr. Gibson said Joe could not go with them. On August 26, Mrs. Gibson drove him back to the Cheyenne railyard. Joe wandered around for several hours before being arrested for vagrancy by railroad detectives George Burnett and Carl Christianson. They thought, due to Joe’s khaki clothing, that he was an army deserter from nearby Fort Logan. He was brought to jail and questioned by the Laramie County Sheriff.

Joe had the unfortunate timing to appear during a widespread manhunt with a $1000 reward on the line. A couple weeks earlier, on August 14, the two Drain sisters were attacked in their home in Pueblo, Colorado. Riley Drain and his wife came home that night to find their daughters’ bedroom “literally soaked in human gore.” Both Dorothy and Barbara, ages 15 and 12, were attacked with a hatchet; Dorothy was also raped. She did not survive, though Barbara did, after being in a coma for two weeks. Neighbors had reported the perpetrator was a “dark, swarthy man,” which meant that everyone was on the hunt for a nonwhite suspect.

The sheriff interrogating Joe, George J. Carroll, discovered that the young (nonwhite) man was a native of Pueblo. He shifted the conversation to the attack on the Drain girls. The sheriff presented leading questions, such as, “You like girls pretty well, don’t you?” followed by, “If you like to go around with girls so much, why do you hurt them?” Joe responded, “Well, I didn’t mean to.” According to Carroll, Joe then fully confessed to attacking the Drain sisters and that he had done it “just for meanness.” After 90 minutes, Carroll called the Pueblo police chief and the local press, reporting Joe as the sole perpetrator in the crime. He told the chief, “[Joe]’s a nut — he can’t even read or write — and he’s told us two or three different stories. But he seems to know all about the Drain murder, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he is the man you want.”

A brief aside: just as people with intellectual disabilities are at higher risk of sexual abuse, they are also at higher risk of giving false confessions. This can be due to suggestibility, communication difficulties, desire to please, not understanding their rights, inadequate access to legal representation, memory deficits, and more. In a 2018 report on exonerated individuals who had given false confessions, 25% met the criteria for intellectual disability, though those with intellectual disability only make up 1-3% of the general population.

The Pueblo chief, J. Arthur Grady, was surprised to hear this, as they had arrested another man, Frank Aguilar, the previous week. Aguilar, an indigenous man from Mexico , had worked for Riley Drain at the WPA and was recently fired. He had been arrested after acting suspiciously at Dorothy Drain’s funeral. Officers then searched his house. Police found an axe head with notches that matched the girls’ wounds, as well as newspaper clippings about the attack, and even a calendar with the date of the attack marked. Scrapings of his fingernails revealed fibers that matched the Drain sisters’ bedsheets. Frank also had a history of violent sexual crimes, though that would not come to light until later. Aguilar finally confessed to the crime on August 28, two days after Joe’s alleged confession.

Conveniently, according to Sheriff Carroll, Joe then provided information that matched up with this new suspect. Joe said that he had been with “a man named Frank” at the crime, though he had at other times said he was alone and staked out in the bushes. Joe had originally said he used a club in the attack, but after another Carroll interrogation, this was changed to a hatchet. Joe also claimed he hid in his family’s home for a week after the crime (though they had moved away while he was committed) and that his mother had burned his bloody clothes. When asked where specifically he had run to, he provided incomplete or incorrect addresses. His family firmly denied that they had seen Joe in years. They were questioned, their home searched and yard dug up.

Carroll, of course, reported a coherent and correct narrative that he had pulled out of Joe. Apparently, though, the contradictions were noted. One newspaper later wrote that Joe had given “an amazing recital of the murder. Though full of contradictions, his story in many respects checked in detail with what the officers knew had happened that night.” The Chieftain even reported that Carroll’s apparently successful interrogation “was eloquent testimony to his shrewdness in drawing a fairly coherent statement from the feeble-minded youth whose warped brain responded clearly on only one subject — women.” The Governor of Colorado also sent a telegram to Carroll, congratulating him on “solving” the case.

Joe was transported secretly to the Colorado State Penitentiary under guard to prevent lynching. He was to meet with Frank Aguilar. The two men were told the other was arrested as an accomplice. Allegedly, upon seeing Aguilar, Joe exclaimed, “That’s Frank!” Aguilar said he had never seen or met Joe before. But, after a nine-hour interrogation filled with questions that always included and/or incriminated Joe, with Aguilar not required to provide any further comments, he signed a statement that Joe had been involved. Joe, who was also present and silent during the interrogation, signed “Arridy.” Both men were characterized in the press as sexual deviants who met by chance and planned the attack. Aguilar later recanted his statement, saying that the interrogators had threatened his life if he did not implicate Joe.

On August 29, Helen O’Driscoll, who had been assaulted in Colorado Springs the previous week, identified Joe as her assailant after seeing his picture at a newspaper. Joe confessed to this upon being asked, even though eyewitnesses and coworkers placed him in Cheyenne at that time, working in the railroad kitchen. A pawnbroker also claimed that Joe had bought a gun from him on the day of the Drain attacks, though this was later dismissed due to the man repeatedly changing the story and not providing any evidence. He had also claimed that Joe had paid in cash, even though he had no money of his own and could not count.

Dr. Jefferson, the superintendent, took full responsibility for the escape of Joe and the other inmates. In a report to the Governor, Jefferson classified Joe as a “high-low” imbecile “due to hereditary influence.” He said that, upon becoming superintendent, he did “everything to improve conditions for both inmates and employees.” As to Joe: “…it should be remembered that the child may have a neurosis or even a psychosis and the conditions may produce conduct disorders which show a moral obliquity.” The newspapers did not look any more kindly on Joe. They called him, among other things: “feeble-minded killer,” “weak-witted sex slayer,” and “perverted maniac.”

Both Joe and Aguilar pled “not guilty” on October 9, 1936. Aguilar’s attorney tried to claim his client was also “feeble-minded,” like Joe, but this did not work. Aguilar was convicted on December 22 and sentenced to death. He was executed on August 13, 1937 in the Colorado State Penitentiary at the age of 34.

Joe’s trial began on February 8, 1937. His lawyer, C. Fred Barnard, pled insanity in hopes to avoid the death penalty. Sheriff Caroll, along with other law enforcement, testified repeatedly that Joe was mentally fit and articulate and accurate during the interrogations, though he had privately called Joe “unquestionably insane.” Three state psychiatrists had determined that Joe was an “imbecile,” meaning he had an IQ of 46 and the mind of six-year-old. One testified that “if it was Joe’s desired to please, he had a tendency to say ‘yes’ to anything with a smile.” The three concluded that Joe “incapable of distinguishing between right and wrong, and therefore, would be unable to perform any action with a criminal intent.” On the stand, Joe’s lawyer allowed the prosecution to ask him several questions related to the case and some that were common knowledge. Joe did not know the difference between coins, did not know what a hatchet was, did not know the current President, and did not recognize his own father in the courtroom, whom he had not seen in eight years by then. He did not know who Dorothy Drain or Frank Aguilar were. He did not show understanding of the trial or being in court. Even given all this, the judge ruled that Joe “was an imbecile, but not insane.”

Joe’s murder trial began on April 12. The jury only deliberated 3.5 hours. On April 17, Joe was convicted of murder, almost entirely due to his false confession/ There was also allegedly physical evidence, a single strand of hair that was determined to be “American Indian,” even though Joe was Middle Eastern (the method used for that hair identification is now discredited). Even Barbara, the surviving Drain sister, had testified in Aguilar’s trial that Aguilar alone had attacked them, not two men. Joe was sentenced to death, but “took no notice of the pronouncement of the death verdict as delivered by the jury foreman.”

For their part in “solving” the case, Sheriff Carroll and the two railroad detectives who had initially arrested Joe were each rewarded $1000 (almost $22,500 in 2025). Dr. Jefferson gave a speech advocating for eugenics while using Joe as an example. He later made a public plea to the Colorado General Assembly to pass a law that would mandate the sterilization of “imbeciles” like Joe. Many of the state’s citizens, hysterical and furious about the whole case, agreed.

Another issue that Joe’s case highlights: the high rates of disability among the incarcerated population today. Approximately 40% of all prisoners have some kind of disability. In a 2016 report, 23% of inmates had an intellectual disability, compared with 1-3% of the general population. As of 2021, this translated to almost 550,000 people with intellectual disability who were in prison. These numbers do not include those who are in jail awaiting trial or serving a sentence of one year or less. These inmates are at much higher risk of being exploited by their fellow prisoners and by staff. Their lack of understanding may make them seem obstinate or stubborn, leading to disciplinary actions. These circumstances can lead to or exacerbate mental illness and violent outbursts.

The warden at the prison, Roy Best, who originally was one of Joe’s interrogators, took a liking to Joe and cared for him “like a son.” He joined the effort to save the young man’s life. He got attorney Gail L. Ireland involved as a pro bono defense counsel for Joe. Ireland won nine stays of execution, but could not get the conviction overturned or the sentence commuted. Even with the overwhelming evidence in Joe’s favor and the support of several professionals, including Dr. Jefferson, to even just commute the sentence, Ireland did not succeed. Catholic clergy also tried petitioning the governor: the prison chaplain, Abbot Leonard Schwin, said, “I don’t think the state ought to execute children.”

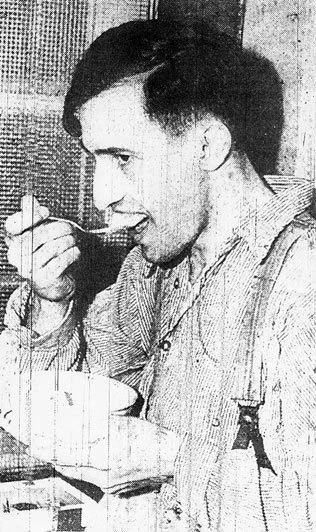

Joe spent almost two years on death row and was beloved by both the inmates and guards. Though on lockdown 23 hours a day, he was cheerful and often laughing. He made funny faces to himself, using a polished metal food tray as a mirror. The warden regularly brought him toys, pictures books, crayons, crafting supplies, homemade candy, and cigars. For Christmas 1938, Best gave him a battery-powered toy train, which became Joe’s favorite toy. He loved crashing it up and down the cells, gleefully yelling, “Car wreck!” His three co-inmates on death row were patient with him, rolling the train back and forth with him from their cells.

One of his execution dates was set for December 25, 1937. When told of that date, Joe’s “befuddled mind grasped only the reference to Christmas, and he smiled,” asking for a watch as a present. This was reported in The Washington Star and an anonymous reader sent a wristwatch as a gift for Joe.

If asked about the execution, Joe said, “No, I am not going to die” or “No, no, Joe won’t die.” Both Best and the prison chaplain repeatedly tried to explain execution to him, but Joe could not understand. When asked once if he wanted to be released, he replied, “No, I want to live with Warden Best…I want to get a life sentence and stay here with Warden Best. At the home the kids used to beat me…I never get in trouble here.” Best later said that Joe was “the happiest prisoner on death row…He probably didn’t even know he was about to die, all he did was happily sit and play with a toy train I had given him.” Joe requested ice cream for his last meal before execution, so Best gave him ice cream for every meal that day.

The final execution date arrived on January 6, 1939. Best opened up Joe’s cell, saying “Come along, Joe. It’s time.” Joe asked brightly, “It’s time for me to go to Heaven?” Best answered, “That’s right.” Joe, only wearing shorts and socks, jumped up eagerly.

Best then surprised him with a visit from his mother, sister, aunt, and a cousin. Joe’s father, Henry, had died of pneumonia two years prior. Mary, his mother, burst into tears and hugged him, though Joe maintained a flat affect during the visit. Other sources do claim that he silently teared up and repeatedly uttered, “Mother.” Most likely, Joe was just quiet and confused. He did get a “slight smile” when inmates brought in a three-gallon bucket of ice cream for the family to share.

The chaplain, Father Schaller, gave Joe last rites, which he could only repeat back two words at a time. The abbot had previously said that he would treat the condemned man “as I do all children who have not reached the age of reason.” He tried to explain to Joe that he would be going on a journey, like a railroad journey, to a heavenly home. Later, when they were trying to convince Joe that he wouldn’t need his toy train anymore, the chaplain told him he would be too busy with his harp to be playing with his train, so he wouldn’t need to take it with him.

Best read the death warrant to Joe and asked if he understood, to which he replied neutrally, “They are killing me.”

Joe shook the hand of every inmate to say goodbye, one of whom broke down into tears. He hadn’t finished his last meal of ice cream, so asked that the leftovers would be refrigerated so he could eat it later. He was upset that he could not take his toy train with him, but eventually agreed to leave it with inmate Angelo Agnes. Joe gifted his polished dinner plate to the warden and his toy car to Best’s nephew, Buddy.

Best walked with Joe up to the gas chamber, a single room shack with a picture window on one side for observers. Joe still smiled after entering, though he was momentarily concerned when he was strapped into the chair and blindfolded. Best held his hand to reassure him before they all had to leave the chamber. 50 people, mostly official witnesses or staff, attended the execution. No member of the Drain family did. Best wept and pled with Governor Teller Ammons to commute Joe’s sentence, but Ammons refused. The cyanide gas was released at 8:13 PM; Joe reportedly was smiling as he lost consciousness after taking three breaths. He was declared dead at 8:19 PM. Joe was 23 years old.

Joe’s story, after sparking so much national interest, then faded into history. The main characters moved on. Two of his death row inmates/friends, including the recipient of his toy train, were executed later that same year. One inmate got a new trial and received a sentence of life in prison, dying in 1950 at the age of 40. Sheriff George Carroll remained Sheriff of Laramie County until 1942 and died in 1961, aged 81. Roy Best remained warden, becoming famous in 1947 for hunting down a group of escapees during a blizzard. He starred in a movie about the incident and then ran unsuccessfully for Governor, dying in 1954 at the age of 54. Gail Ireland served as Attorney General of Colorado during World War II and then as Colorado Water Commissioner. He died at age 92 in 1988. His granddaughter published a book about him, Gail Ireland, Colorado Citizen Lawyer, in 2011.

The Drain family did not fare as well. When reading about them, I couldn’t help but think that they were cursed. Riley Drain’s first wife, Minnie, had died in 1929, leaving him a widower with three children aged two, five, and eight. Two years later, Drain married Emma Martinez, who became the children’s stepmother. The horrific attack on the girls occurred in 1936: Dorothy was three months shy of 16 and Barbara was only one month from her 13th birthday. Tragically, Billy also died young: he was 17 when, in 1944, he died of a spinal cord injury obtained during football practice. Riley lived until 1958 and Emma until 1964. Barbara was the only survivor: she reportedly married Earl “Kit” Carson, a career Air Force officer, with whom she had four sons and three daughters. He died in 1999 and she lived until 2002, dying at the age of 78.

Mary Arridy, Joe’s mother, moved to live with her brothers in Toledo, Ohio in 1947, adopting their last name spelling of “Areddy.” She died in 1960, aged 75. Joe’s brother George was forcibly committed to the same school Joe had been in. He was never paroled, given the infamy of his brother. He died sometime after 1950, but no one knows when or where. Their sister Melia married a soldier, John Gannon, in 1945 and moved to Memphis, Tennessee. They had a son and two daughters, one of whom died young. Melia died in 2012 at the age of 88. She was the only one of these main characters who lived to see Joe exonerated.

In 1992, sociologist Richard Vorhees discovered a 1944 poem “The Clinic” by Marguerite Young in an out-of-print book. It was about the final interaction between a warden and an inmate about to be executed. He sent the poem to author Robert Perske, an advocate for people with disabilities, who in turn consulted with archivist Watt Espy. Espy, an expert on capital punishment, identified the poem as being about Roy Best and Joe Arridy. Perske was ignited after hearing about Joe’s case and spent the next few years researching across Colorado. He published the book Deadly Innocence? in 1995. This book started a movement in support of Joe. Screenwriter Dan Leonetti wrote a script based on the book and won national awards.

In 2006, the Arc of the Pikes Peak Region opened its doors to all who had worked on Joe’s case and who cared about what had happened to him. They even provided funding. The following year, the group became known as “The Friends of Joe Arridy.” They collected money to replace Joe’s grave marker (a rusty motorcycle license plate labeled “ARRDY”) with an actual tombstone. Attorney David A. Martinez attended the dedication ceremony and was inspired. He prepared a 523-page petition for pardon from Governor Bill Ritter. Ritter gave Joe a full and unconditional pardon on January 7, 2011, saying, “Pardoning Joe Arridy cannot undo this tragic event in Colorado history, it is in the interests of justice and simple decency, however, to restore his good name.” It is the first and only posthumous pardon ever in Colorado.

On May 19, 2011, another dedication ceremony was held at Joe’s grave. Additional sentences had been chiseled into the tombstone. The left one read, “PARDONED ON JAN. 7, 2011.” On the right it was written, “HERE LIES AN INNOCENT MAN.”

It is worth ending with “The Clinic,” the poem that, when discovered decades after it was written, sparked the movement to pardon Joe.

“The Warden wept before the lethal beans

Were dropped that night in the airless room,

Fifty faces apeering against glassed screens,

A clinic crowd outside the tomb.

In the corridor a toy train pursued

Its tracks past countryside and painted station

Of tinny folk. The doomed man’s eyes were glued

On these, he was the tearless one

Who waited unknowing why the warden wept

And watched the toy train with the prisoner

Who watched the train, or ate, or simply slept.

The warden wrote a sorry letter,

“The man you kill tonight is six years old,

He has no idea why he dies,”

Yet he must die in the room the state has walled

Transparent to its glassy eyes.

And yet suppose no human is more than he,

The highest good to which mankind attains

This dry-eyed child who watches joyously

The shining speed of toy trains,

What warden weeps in the stony corridor,

What mournful eyes are peering through the glass,

Who will ever shut a final door

And watch the fume upon a face?”

Most sincerely,

ChristinaFurther Reading

Deadly Innocence? by Robert Perske

Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition by Liat Ben-Moshe

Intellectual Disability and the Criminal Justice System: Solutions Through Collaboration by William B. Packard, Ph.D.

Autism Spectrum Disorder, Developmental Disabilities, and the Criminal Justice System: Breaking the Cycle by Nick Dubin

Works Consulted

Breitenstein, M. (2015, October 27). The Dark History of an Abandoned Institution. Denver Public Library Special Collections and Archives. https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/western-history/dark-history-abandoned-institution

Curtis IV, E. E. (2022, December 15). Syrian Quarter. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. https://indyencyclopedia.org/syrian-quarter/

de Yoanna, M. (2010, October). Crime: Begging Joe’s Pardon. 5280. https://5280.com/crime-begging-joes-pardon/

Death Penalty Information Center. (2011, January 11). Colorado Governor Grants Unconditional Pardon Based on Innocence to Inmate Who Was Executed. Death Penalty Information Center. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/colorado-governor-grants-unconditional-pardon-based-on-innocence-to-inmate-who-was-executed

Dimuro, G. (2021, October 30). Joe Arridy: The Mentally Disabled Man Executed For A Grisly Murder He Didn’t Commit (J. Kuroski, Ed.). All That’s Interesting; All That’s Interesting. https://allthatsinteresting.com/joe-arridy

Disability. (2025, October 15). Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/research/disability/

Dr. Jefferson Tells Story of Arridy Escape. (1936, September 16). The Rocky Mountain News, 15. https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=RMD19360916-01.2.204&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7CtxCO%7CtxTA--------0------

Get the Facts About Sexual Violence Against People with Disabilities. (2025, October 9). RAINN. https://rainn.org/get-the-facts-about-sexual-violence-against-people-with-disabilities/

Here’s More About Arridy... (1939, January 6). The Daily Sentinel, 11. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-daily-sentinel/59778444/

Joe Arridy: The Mentally Disabled Man Executed for a Murder He Never Committed. (2024, January 27). Rare Historical Photos. https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/joe-arridy/

“Man” Happily Leaves Toys for Death in Gas Chamber. (1939, January 7). The Pittsburgh Press, 1. https://books.google.com/books?id=f00bAAAAIBAJ&dq=arridy&pg=PA1&article_id=2382,1678573#v=onepage&q=arridy&f=false

Maruschak, L., Bronson, J., & Alper, M. (2021). Disabilities Reported by Prisoners (pp. 1–10). U.S. Department of Justice. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/drpspi16st.pdf

McShane, T. (1941, July 13). The Murder of Dorothy Drain. St. Petersburg Times, 33–34. https://books.google.com/books?id=_EJPAAAAIBAJ&dq=arridy+carroll&pg=PA34&article_id=2355,864472#v=onepage&q=arridy%20carroll&f=false

Perske, R. (n.d.). Chronology. Friends of Joe Arridy. Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://friendsofjoearridy.com/chronology/

Perske, R. (1995). Deadly innocence? Abingdon Press.

Precautions taken to prevent lynching feeble-minded youth who admits murder in Pueblo. (1936, August 27). Greely Daily Tribune, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/article/greeley-daily-tribune-1936-aug-27-prec/3345921/

Prendergast, A. (2012, September 20). Joe Arridy Was the Happiest Man on Death Row. Denver Westword; Denver Westword, LLC. https://www.westword.com/news/joe-arridy-was-the-happiest-man-on-death-row-5118031/?storyPage=4

Sarrett, J. (2021, May 7). US prisons hold more than 550,000 people with intellectual disabilities – they face exploitation, harsh treatment. The Conversation; The Conversation US, Inc. https://theconversation.com/us-prisons-hold-more-than-550-000-people-with-intellectual-disabilities-they-face-exploitation-harsh-treatment-158407

Schatz, S. J. (2018). Interrogated with Intellectual Disabilities: The Risks of False Confession. In Stanford Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities Law and Policy Project (pp. 643–690). Stanford Law School. https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Samson-Schatz-Interrogated-with-Intellectual-Disabilities-The-Risks-of-False-Confession.pdf

Wadlington, S. (2025, April 4). The Pardon of Joe Arridy. True Crime Story Blog. https://truecrimestoryblog.com/blog/f/the-pardon-of-joe-arridy?blogcategory=True+Crime+Story:+Shorts

Warden, R. (2014). ARRIDY. Friends of Joe Arridy. https://friendsofjoearridy.com/articles/

Young, M. (1944). The Clinic. In Moderate Fable. Reynal & Hitchcock.

Last Updated: 17 Oct. 2025