Brad Lomax - A Bridge

I admit that, though I have been involved in the disability community for my entire life, I have only recently gained any knowledge of the disability activists of the past several decades. It is because of them that my sister is able to access buildings in her community, obtain an education, and more. Many of these activists are not well-known, especially ones of color. Brad Lomax is considered one of the founders of the intersectional activism that combined the resources of the civil rights movement with the disability movement's fortitude.

Brad at a rally, 1977

Bradley (sometimes reported as Bradford) "Brad" Clyde Lomax was born on September 13, 1950 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the oldest of three children. His parents were Katie Lee (née Bell) and Joseph Randolph Lomax. He was described as a typical child who enjoyed Boy Scouts, football, and theater. Due to living in the northern United States, he was reportedly unaware of codified racial segregation until the age of thirteen. He visited relatives Alabama which, in 1963, prominently displayed signage for segregated public spaces. The blatant and militant racism created the spark of activism in the young teenager.

After graduating from Benjamin Franklin High School in 1968, Brad planned to join the military and fight in the Vietnam War. However, knowing that Black soldiers received much poorer treatment in the military, he instead attended Howard University. This was also the year that his health changed dramatically. He began falling as he walked and was eventually diagnosed with Multiple sclerosis (MS). The disease progressed rapidly, and he soon began using a wheelchair. This is when he discovered how unavailable the world was: for instance, most public buildings lacked ramps, making them inaccessible. People with disabilities were denied education, jobs, and housing, especially if they were also Black.

The following year, in 1969, Brad helped found the Washington D.C. chapter of the Black Panther Party (BPP). This organization had reached its peak the year before with roughly two thousand members. The BPP was his primary focus for the next few years. His major accomplishment was helping organize the first African Liberation Day demonstration on the National Mall in 1972.

Brad and his brother, Glenn

Brad's brother, Glenn, lived in Oakland, California at the time. Brad decided to move west too and join the disability rights movement. He was motivated to action immediately after attempting to use public busing: his brother had to carry him from his wheelchair to a bus seat then go back for the wheelchair and haul it aboard.

In 1974, Brad began serving at the George Jackson Clinic. This clinic was funded by the Black Panthers and consisted of volunteer doctors and nurses who provided free medical services to the community. A 1974 memo from the clinic reported that, "Brad Lomax because of his restricted movement is the public relations co-coordinator of the clinic. Also meeting with people to set up functions and relationships with people who can be of a benefit to the clinic."

Brad and his brother, Glenn, at the Oakland Black Panther headquarters, 1974

Perhaps Brad's greatest achievement was building a bridge between the disability and Black rights movements. It was at the clinic that he met Ed Roberts, director of the Berkeley Center for Independent Living (CIL). Donald Galloway, one of the first Black leaders in the CIL movement, remembered:

“There was a severely disabled man in the Black Panther Party named Brad, and Brad was our link to the Black Panthers. We would go and provide him with attendant care and transportation because we had a small transportation system going, a fleet of vans going out to the community. Ed made a decision that he wanted us to get more involved with the Black Panthers and with Oakland. So we would go to some of their meetings and explain our programs. Because Brad, one of their members, had a severe disability, we were quite accepted.”

Brad, knowing that the current center primarily served white people, proposed another location, funded by the Black Panthers, in East Oakland to serve the Black disabled communities there. Both the CIL and BPP approved this new center. It gave much-needed services to East Oakland and, in turn, helped the BPP be more active in housing and transportation issues relating to the discrimination against the disabled and elderly. Brad served as one of the two-person staff at the East Oakland CIL, providing basic peer counseling and attendant referral. However, the Oakland center only operated from 1975-1977, due to limited support from the both the BPP and Berkeley CIL. Mary Lester, the Berkeley CIL's receptionist at the time, described the issue: "It was really at a distance, which was one of the problems in terms of its being successful. Also, you know, CIL wasn't at all familiar with that culture or that community and they sort of plunked this thing down and really didn't understand how to make it work very well, so it was fairly short-lived." On the BPP's end, they appeared indifferent to making "independent living" a central feature in their freedom struggle. This lack of participation may also have been due to troubles the Party was facing at this time, including leadership resignations, lawsuits, and a murder trial.

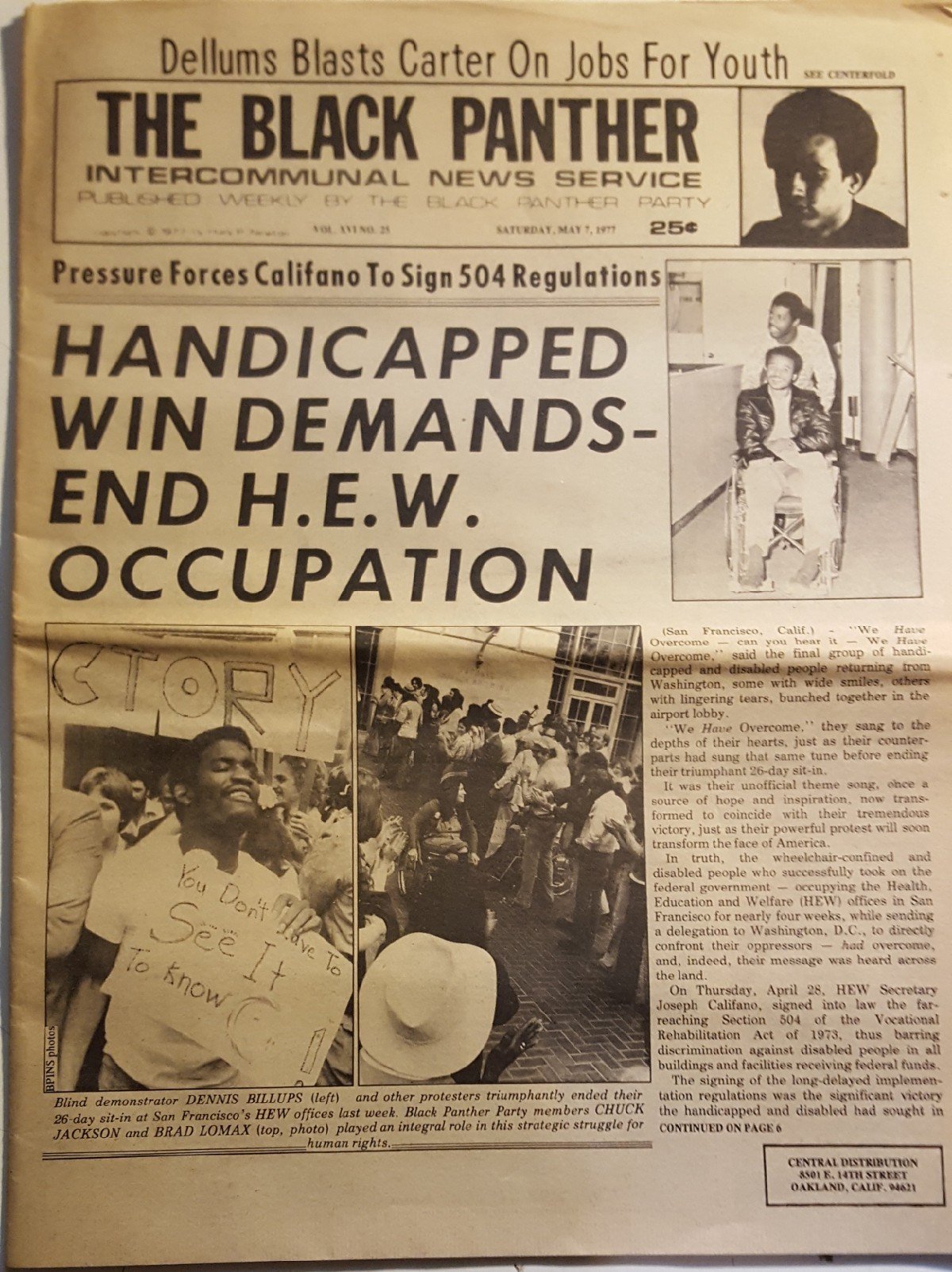

As discussed in my post about Ed Roberts, at this time disability activists led the way by holding demonstrations to enforce section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This stated that “no otherwise qualified handicapped individual in the United States shall solely on the basis of his handicap, be excluded from the participation, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.” They held a 28-day sit-in, the only successful one of many held across the country, at the offices of the Carter Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) in San Francisco in 1977. Over 300 activists participated in the longest non-violent occupation of a federal building in US history. Cece Weeks, a protest leader, told reporters, "It’s the first really militant thing that disabled people have ever done. We feel like we’re building a real social movement and we want people to listen to us. We have tried negotiations. They do not work. At this point, we are non-negotiable."

The protestors were not expecting the sit-in to last so long, so many did not have essentials such as toothbrushes, extra clothes, and food. Due to Brad's involvement during the entire sit-in, the Black Panthers supported all of the protestors, as they were also being denied access to phone lines, hot water, and backup ventilators. Another Black Panther, Chuck Jackson, provided personal care for Brad and many other protestors. Along with publicly endorsing the protest, the Party was committed to providing hot meals every single day of the sit-in, saying, "We support you because you're asking America to change, to treat you like human beings, like you belong. We always support people fighting for their rights." When FBI agents guarding the entrance asked what the Black Panthers were doing delivering food to the protestors, they reportedly answered, "Listen, we’re the Panthers. You want to starve these people out, fine, we’ll go tell the media that that’s what you’re doing, and we’ll show up with our guns to match your guns and we’ll talk about who’s going to talk to who about the food. Otherwise, just let us feed these people and we won’t give you any trouble." The BPP was allowed to continue its work unhindered. A protestor stated that, "without that food, the sit-in would have collapsed." Judy Heumann, another demonstration leader, called Brad the "linchpin" of the collaboration.

Brad during the 504 protests, 1977

The BPP also helped publicize the protest and gain community support. An article from the Black Panther contained a call to action from Dennis Billups:

“To my brothers and sisters that are Black and that are handicapped: Get out there, we need you. Come here, we need you. Wherever you are, we need you. Get out of your bed, get into your wheelchair. Get out of your crutches, get into your canes. If you can’t walk, call somebody, talk to somebody over the telephone; if you can’t talk, write; if you can’t write use sign language; use any method of communication that is all — all of it is open... We need to do all we can. We need to show the government that we can have more force than they can ever deal with …”

This sit-in intentionally linked themselves to the Civil Rights movement of the decades previous, including borrowing those earlier freedom songs, such as "We Shall Overcome." Corbett O'Toole, a disabled activist also present for the entire protest, said,

“By far the most critical gift given us by our allies was the Black Panthers’ commitment to feed each protester in the building one hot meal every day…. The Panthers’ representative explained that the decision of Panthers Brad Lomax and Chuck Jackson to participate in the sit-in necessitated a Panther response…. and that if Lomax and Jackson thought we were worth their dedication, then the Panthers would support all of us. I was a white girl from Boston who’d been carefully taught that all African American males were necessarily/of necessity my enemy. But I understood promises to support each others’ struggles.”

Brad & Judy Heumann at a rally in Washington, D.C., 1977

After two weeks of protest, Brad, Jackson, and two dozen out of the 150 protestors were sent as the delegation to Washington, their travel paid for by the Black Panthers. They advocated to everyone they came across, including the HEW Secretary Joseph A. Califano Jr. (they sat outside his house) and President Jimmy Carter (who ran out of a side door of his church to avoid them). They met with other Senators, urging them to increase pressure on Califano. Finally, on April 28, 1977, Califano signed the regulations. Two days later, the victorious protestors returned home. Activist Kitty Cone later remembered, "We had shown ourselves and the country...that we, the most hidden, impoverished, pitied group of people in the nation, were capable of waging a deadly serious struggle that brought about profound social change."

The Black Panther newspaper, featuring Brad & Chuck Jackson in the upper right

After the sit-in, Brad continued to do some work with the BPP, perhaps even until its formal end in 1982 (when the last Panther school closed amid an embezzlement scandal). At its end, it had fizzled to about 27 members. Billups said of Brad, "I don’t think that all of his aspirations were fulfilled, even after the demonstration. He really wanted more." It appears that he was physically unable to do much more: some sources suggested that the strain of the 504 protests and travel had a substantial impact on his health. He died from complications of MS on August 28, 1984 in Sacramento, California. He was two weeks shy of his 34th birthday.

Brad celebrating his birthday with friends in San Francisco, 1981

As with so many of my stories, it is the arts that brought Brad Lomax back into public view. In March 2020, he appeared in the documentary Crip Camp, currently streaming on Netflix. That same year, in July, he was also featured in The New York Times "Overlooked" obituary series. Perhaps the best epitaph for Brad comes from a 1977 article: the Black Panther Intercommunal News Service reported, "A young Black woman came up to Brad Lomax, a Black Panther Party member victimized by multiple sclerosis, upon his return from Washington, and embracing him in his wheelchair remarked, 'Thank you for setting an example for all of us.'"

Most sincerely,

ChristinaFurther Reading

On the Black Panther Party

Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party by Waldo E. Martin & Joshua Bloom

The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History by David F. Walker & Marcus Kwame Anderson

Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination by Alondra Nelson

On the Disability Rights Movement

Disability Rights Movement by Tim McNeese

Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist by Judith Heumann & Kristen Joiner

What We Have Done: An Oral History of the Disability Rights Movement by Fred Pelka

Media of Interest

"Brad Lomax - Celebrating Black History & People with Disabilities" (2018) on YouTube

"A Brief Recounting of the 504 Sit-In" (2020) on YouTube

"The Power of 504" (1997) on Vimeo

An episode of the Good Black News Daily Drop Podcast

Works Consulted

Brad Lomex: The Black Panthers and the Disability Rights Movement. (2022, February 11). DisHistSnap. https://www.disabilityhistorysnapshots.com/post/brad-lomex-the-black-panthers-and-the-disability-rights-movement

Connelly, E. A. J. (2020, July 20). Overlooked No More: Brad Lomax, a Bridge Between Civil Rights Movements. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/08/obituaries/brad-lomax-overlooked.html

Dawson, D. (2022, February 16). Brad Lomax and the Americans With Disabilities Act. McCormick Theological Seminary. https://www.mccormick.edu/herald/brad-lomax-and-the-americans-with-disabilities-act

Jones, T. (2022, February 2). Brad Lomax: How the Black Panthers and Disability Movement Came Together. Just a Little. . . https://justalittlepod.com/blog/brad-lomax-black-panthers-disability

Lomax’s Matrix: Disability, Solidarity, and the Black Power of 504 | Disability Studies Quarterly. (n.d.). https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/1371/1539

Now, I. (2022, February 22). Black History Month Profile: Bradley Lomax. Independence Now. https://www.innow.org/2022/02/22/black-history-month-profile-bradley-lomax/

Spectre. (2021, June 7). The Intersections and Divergences of Disability and Race –. Spectre Journal. https://spectrejournal.com/the-intersections-and-divergences-of-disability-and-race/

Thompson, V. L. (2017, February 17). Black History Month 2017: Brad Lomax, Disabled Black Panther. Ramp Your Voice. http://www.rampyourvoice.com/black-history-month-2017-brad-lomax-disabled-black-panther/

“We Want 504!” (2022, April 1). Boundary Stones. https://boundarystones.weta.org/2021/10/12/we-want-504

Last Updated: 23 Sept. 2023